From Blockage to Breakthrough

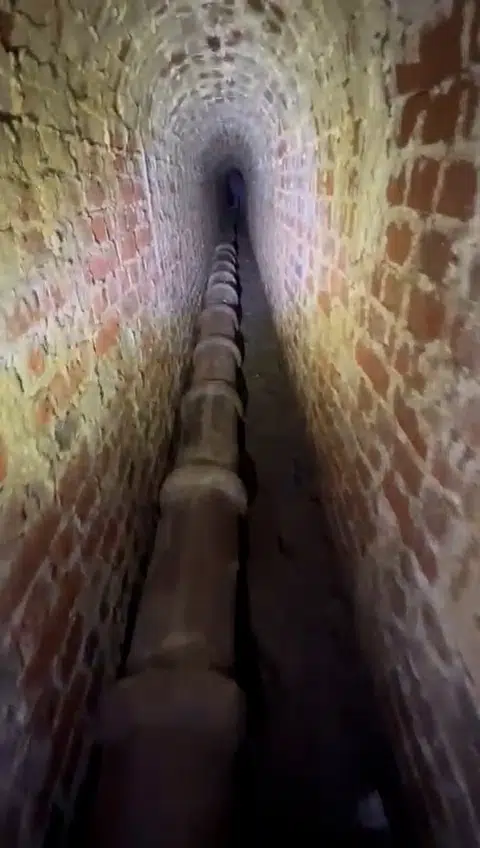

The first time you duck into the drainage tunnels under a Grade I listed property, you clock two things right away. One, space is tight. Two, the air feels heavy with age. Puslinch House in Devon has that in spades. We were called here for a stubborn blockage, but as soon as we looked down that first access, we knew the job was going to be about more than just getting the water moving again. This isn’t just plumbing. Down here, the drains aren’t just pipes, they’re part of the house’s story. Three centuries of it.

How do you even start unblocking drains in a listed property?

The basics are the same: find the blockage, clear it. The difference is in how you do it.

When we arrived, the signs were clear enough. Slow flow, a bit of pooling, and that faint but telling smell you get when waste starts backing up. But with Puslinch House, we weren’t looking at one system, we were looking at three, layered on top of each other. Georgian brick. Victorian clay. 1970s concrete. All in the same run.

The first access point was no easy climb-down. If you’ve watched our Drain Unblocking in a Stately Devon Home, Part One, you’ll know it’s not somewhere you’d want to get stuck. Narrow brick tunnel, cool damp air, the sound of your own breathing loud in your ears. You tread carefully here, because one misplaced boot could knock a brick that’s been sitting happily in place for 300 years.

We started simple. Drain rods, steady and slow. You can’t rush an old system, not unless you want to add “collapsed culvert” to your problem list. Newer builds? We’d be tempted to go straight for the jetter. Here, we held back.

When Georgian grit meets Victorian ingenuity

It didn’t take long to feel resistance. The rods stopped just after a change in the sound and feel, a soft clink against clay. We’d found the join where Victorian pipe meets Georgian culvert. That’s a trouble spot in a lot of heritage systems. The brick drains were built for slow gravity flow, but once the Victorians slid their smooth glazed clay into the network, those junctions became natural catch points for debris.

The camera didn’t lie, there it was, a cracked interceptor trap. Judging by its build, almost certainly Victorian. Back then, these traps were considered cutting-edge, a clever way to stop foul air sneaking back indoors.

This one? Well, let’s just say it had been through a few winters. The crack was big enough to let silt drift in from the surrounding ground, and over time it had mixed with waste until we had the mess sitting in front of us.

Getting it moving again

This wasn’t the sort of job you solve in one push. We worked the rods in a little, then pulled back, over and over, chipping away at the blockage instead of trying to blast through. Between stages, we used low-pressure jetting, just enough to coax the debris forward. Too much force and you risk shaking the old Georgian brickwork loose.

If you’d been standing where we were, you’d have seen the water change. At first it swirled in that cloudy, murky way that tells you nothing’s going anywhere fast. Then, slowly, the trickle picked up. The smell shifted too. Still not pleasant, drains never are, but sharper, cleaner, with the sour edge gone.

The last bit to come free had soil mixed through it. That told us the crack wasn’t just cosmetic; the drain had been open to the earth for a long while. The flow was back, but that damaged trap was still a problem waiting to happen again.

Puslinch House isn’t the only one with a story like this. Across Devon, the timeline’s similar.

1720s – Georgian era

Out in the countryside, big estates built their own drainage. Brick culverts running to cesspits or soakaways, with no link to any main sewer, mainly because such things didn’t exist yet outside of larger towns. Plymouth had some early street drains, but in places like this the night soil man or the estate’s own staff kept the system moving.

Mid- to late-1800s – Victorian changes

Public health reform meant smoother clay pipes, better gradients, and, yes, traps like the one we’d just been working on. Puslinch probably had its upgrades around the same time as Tavistock or Totnes, when new drainage laws and technology were changing how waste was handled. The old brick sections stayed in service though, joined to the new.

1970s – Concrete steps in

By now, reinforced concrete chambers with steel footholds had become the go-to. Strong, practical, and far easier to work in. The catch? They were often dropped into existing layouts, so you’d have modern chambers feeding into Victorian pipe, which in turn met Georgian brick. One run, three centuries of design quirks.

Why jobs like this drag on longer than you’d think

With new drains, it’s pretty straightforward. Same size all the way through, one type of material, and they slot together like flat-pack furniture. Old drains? They’re a different beast. Every section’s built from something else, and each bit behaves in its own way. Push too hard with rods and you can crack a clay run. Jet in the wrong place and you risk loosening mortar from a brick joint, once that happens, you’ve got a bigger mess than when you started.

At Puslinch House, we kept it slow. Camera in, rods forward a bit, camera back in. It’s stop–start work, but it means you don’t get nasty surprises later. Truth be told, it’s not about finishing in record time, it’s about making sure you’re not back again two weeks later because half the drain’s caved in.

You Asked, We Answered – Historic Drain Care

Yes, but only after we’ve checked it over properly, and we’ll turn the pressure right down.

They’re tighter in diameter, have more joins, and some aren’t perfectly smooth inside. It doesn’t take much for bits and pieces to settle and stick.

We do, all over Devon, Cornwall and Plymouth. Everything from tucked-away farmhouses to big estate houses like Puslinch.

Respecting the past while fixing the present

Working on a drainage system like Puslinch House isn’t just about clearing a blockage. It’s about understanding the history beneath your boots, knowing how each era built its drains, and making sure your modern repairs don’t undo centuries of work.

That’s why heritage drain jobs cost more and take longer, you’re not just paying for labour, you’re paying for expertise that keeps the old running alongside the new.

Contact Us